STONINGTON IN REBELLION, 1775

A Special 350th Anniversary Article

By Norman F. Boas

(From Historical Footnotes, May 1999)

Dr. Norman F. Boas, former president and former librarian of the Stonington Historical Society, is an authority on the Revolution in Stonington and coastal Connecticut, and is the author of Stonington During the American Revolution (1990). In February 1999, he delivered one of the series of special lectures marking Stonington's 350th anniversary, centering on what could be called the First Battle of Stonington, the British attack of 1775. Here is his account.

In 1855 Benson Lossing, author of an encyclopedic book on the American Revolution, wrote, "Stonington is a thriving town . . . settled by a few families about 1658 . . . It has but little Revolutionary history except was common to other coast towns, where frequent alarms kept the people in agitation. . ."

Stonington deserves more than a one-sentence commentary on its role in the War for Independence. Southeastern Connecticut saw more military action than any other section of the colony. Stonington was the first coastal town in America to fend off a British attack. There were raids on Fairfield, Danbury, and New Haven, but Stonington, Groton, and New London were the sites of the only battles in Connecticut during the Revolution.

Stonington's unique and strategic military position was that of being the only Connecticut town on the Atlantic Ocean and the gateway to Long Island Sound. More than 330 men from Stonington served in the Revolution, and they saw action in virtually every battle. They included a number of blacks as well as Indians.

At the beginning of the Revolution Stonington had a population of more than five thousand, which included 237 Indians, more than any other Connecticut town, and 219 blacks. About five hundred persons lived on Long Point, the present Borough. Stonington had three protected harbors, at the Point, and in the Pawcatuck and Mystic rivers. Before the war many local shipowners were engaged in the West India trade, exporting cattle and other livestock and importing spices, sugar, molasses, and rum.

Supporting Boston

In the years before the Revolution, Stonington's residents found themselves in an ambivalent position, loyal to the Crown but saddened and disillusioned by British actions that threatened their freedom. For many years, the Crown provoked the colonists with repeated efforts to raise taxes.

In 1772, Samuel Adams, reacting to the Crown's takeover of the Massachusetts judicial system, created "committees of correspondence," an underground communications system between towns and colonies for sharing information. By 1773, most of the towns and all of the colonies had set up committees. Stonington selected eleven citizens for its committee. In 1774, members of the committees were selected as delegates to the First Continental Congress.

The ultimate provocation occurred in 1773 after ships of the East India Company arrived in Boston, Philadelphia, New York, and even New London, carrying tea that was subject to British taxation even before unloading. In New London, the tea was seized and burned; in Boston produced its famous Tea Party. In response, the British closed the Port of Boston and nullified the provincial government.

In May 1774 the Connecticut Assembly was informed of the Boston Port Bill and passed resolutions supporting the Bostonians. On July 11, 1774, the voters of Stonington voted that the Resolves of the General Assembly be recorded in the Town Book. They may be read today in their original form at the Town Hall. At the same meeting, Stonington passed a resolution supporting Boston. In response they received a letter from Joseph Warren, chairman of the Boston Committee of Correspondence, a signal honor. Stonington also passed a resolution to ban the import of goods from Great Britain, the second Connecticut town to do so.

The Lexington Alarm

In 1775, the future rapidly became more ominous. State and local militia were organized, mustered, and drilled. On April 19, 1775, the British, seeking the "traitors" Samuel Adams and John Hancock, engaged the patriots in Lexington and exchanged fire; the war was on. Israel Bissell, a post rider, was dispatched at 10 a.m. on April 19 to Connecticut to alert the countryside to the "Lexington Alarm." He arrived at Norwich at 4 p.m. the next day and reached New London by 7. Stonington must have learned the news the same evening.

So inflamed was the response that nearly four thousand Connecticut minutemen from nearly fifty towns immediately took up arms and marched to Massachusetts. The Lexington Alarm list from Stonington included Benjamin Park, Nathaniel Minor, Rev. Nathaniel Eells, and Nathaniel Palmer (probably the grandfather of Captain Nathaniel B. Palmer).

By May 1775, Connecticut had organized twenty-eight militia regiments, totaling 23,000 men. In July 1775, the Continental Congress authorized the formation of the Continental Army, and on July 2 George Washington arrived in Cambridge to take command. Many Stonington men served at Boston in regiments commanded by Colonel Samuel Holden Parsons and Colonel Jedediah Huntington. Other Stonington men served in Captain Nathan Hale's company on Long Island Sound.

It was not long before Washington established a firm land blockade of Boston. With thousands of British troops and Tories trapped there, shortages of food developed rapidly, and the British organized raiding expeditions along the coast. They were in control of Newport, Rhode Island, which gave them a port of refuge near the gateway to Long Island Sound.

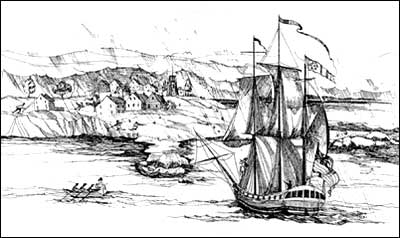

British Admiral Graves dispatched Captain James Wallace to the shorelines of Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Long Island to obtain cattle, other livestock, and provisions, and to establish a sea blockade. At this time Wallace was in command of the Rose, a 20-gun frigate, with two tenders, theSwan and King-Fisher. Wallace was a man of few scruples and little honor in his treatment of American patriots. In June 1775 he plundered the shoreline of Narragansett Bay and the port of Newport and cruised up and down Long Island Sound purging it of American craft by gunfire and acts of piracy.

One of his first incursions into Long Island Sound was on July 26, 1775, when his ships blockaded New London and damaged the lighthouse. They next descended on Fisher's Island, taking cattle, about 1,100 sheep and other provisions. In response, the state's Council of Safety activated militia troops in Stonington, New London, and Groton. The ship available for defense was the Britania, owned by Edward Hancox, John Denison 5th, and others in Stonington. The Council purchased and armed it with cannon and other armaments and renamed it the Spy. It played a major role in Connecticut's Continental Navy for several years.

Defending the Point

Wallace's piratical acts continued along the shores of Long Island during the month of August. The inhabitants of Block Island became anxious and fearful that they might also lose their stock and worldly goods to the British. They had good reason to be concerned, for the island was unprotected and twelve miles out at sea. Some time in August, they shipped their cattle in a fleet of small vessels across Block Island Sound to Stonington. The cattle were put ashore to pasture on the plains of Quanaduck, on Stonington's inner harbor.

Alerted by local Tories to the transfer of Block Island cattle, Captain Wallace arrived in Stonington harbor at 7 a.m. on August 30, 1775, on his vessel, the H.M.S. Rose, with three tenders, purportedly to confiscate the cattle. The ships arrived without colors. When Captain Oliver Smith, who was in command of a militia company at the Point, ordered that the men in the tenders be hailed, the only answer was a volley of fire from their cannons. Word of the arrival of the British ships quickly spread along the Point and to the countryside.

Captain William Stanton gathered his company together near the Road Meeting House, and marched three miles to the Point. Included in his company were Sergeant Amos Gallup, William Denison, George Denison, and about seventeen other minutemen. They joined forces with Captain Smith's company, and all marched to Brown's wharf on the east side of the Point, where they took their positions.

In the meantime, the tenders made their second approach and attempted to steal two ships in the harbor; they were repulsed with musket fire. After this retreat, the Rose and its three tenders formed a line of battle and commenced a bombardment, under cover of which they were able to carry off a sloop and a schooner. The cannonading continued all morning. Upon its cessation, Captain Smith sent a message to Captain Wallace seeking an accommodation. Wallace refused and resumed bombarding the town broadside until dusk. The local militia were able to hold off approaches of the British by firing their Queen Anne muskets. During the battle many women and children were forced to leave their home and march inland in mud and driving rain. Wallace's ships left that evening.

According to newspaper accounts, "our enemies, at the moderate Account, fired nearest a Thousand cannon and Swivel guns, besides small arms, damaged a great many houses, killed not one person and wounded but one of our men." The casualty was Jonathan Weaver, Jr., a private in the militia. After the battle, the General Assembly awarded him £12-4-4 as compensation for his injuries.

Captain Wallace's attack on Stonington was the second British naval assault on the shores of the American continent during the American Revolution, the first occurring in Boston Harbor on June 17, 1775. Further, the attack on Stonington was the only naval attack on the shores of Connecticut during the Revolution, and the first time a British naval force was repulsed by the colonists.

On September 15, 1775, sixteen days after the battle, Governor Jonathan Trumbull wrote to General Washington, advising him that Stonington had been attacked and severely cannonaded, and "by Divine Providence marvelously protected." Washington remarked that "the spirit and zeal of Connecticut were "Unquestionable."

Some time after Wallace's attack, Stephen Peckham, a Tory, was charged with piloting the H.M.S. Rose for Wallace into Stonington harbor. He was captured and brought to Stonington Point for punishment. Peckham was ordered to stand under a large tree on the Point called the Liberty Tree to face his accusers. His written confession was read to a large gathering of local residents. This was deemed to be just, and was his only punishment.

Evidence of the attack remained for many years as scars on houses in Stonington. Most had patches and repairs from direct hits. Cannon balls were discovered and retrieved for a long period after the assault. Some still remain in the Borough as souvenirs of the first British attack on Stonington.

As a result of the attack on Stonington the General Assembly and the Continental Congress intensified their war efforts and Connecticut formed its own Continental Navy. In 1776 fortifications were built along the coast, including Fort Trumbull in New London and Fort Griswold in Groton, named for the governor and lieutenant governor respectively. Congress also formulated rules permitting privateering against enemy vessels.

Thereafter, Stonington men participated in all phases of the American Revolution. They built and commanded ships; they manned privateers that intercepted and captured British vessels. For the war effort Stonington's inhabitants manufactured saltpeter, crushed cornstalks in their mills to make molasses and rum; they prepared salt from sea water; they raised crops, wove cloth, and supplied many other provisions. They lost fathers, sons, and grandchildren and fought in virtually every battle against the British--on their own soil at Long Point, at the bloody encounter at Fort Griswold in 1781, and throughout the countryside.