THE STATELY HOMES OF LAMBERT'S COVE:

The Legacy of Gamaliel King, 1795-1875

By Mary M. Thacher

(From Historical Footnotes, February 2001)

Mary M. Thacher is the archivist of the Stonington Historical Society and Stonington Town Historian. Here she recounts the wide-ranging inquiry that led to her conclusion that four of the grandest nineteenth-century houses in Stonington, including the Captain Nathaniel B. Palmer House, were the work of a single New York architect.

(Click here to see photographs of the four homes.)

Four stately homes were built in the 1850s near the shores of Lambert's Cove, just north and west of Stonington Borough, by a group of entrepreneurs who shared family and business connections, many in New Orleans. One of these houses is now a National Historic Landmark -- the Captain Nathaniel B. Palmer House, a property of the Stonington Historical Society.

These houses were not included in Grace D. Wheeler's compendious Homes of Our Ancestors in Stonington, Conn., perhaps because of their owners' connections with the South. At the time of publication, 1903, the Civil War remained a wound in the memories of people who had lost loved ones. Or perhaps Grace Wheeler considered houses that were only fifty years old too new to include.

My interest in these houses began more than ten years ago, when I received a letter from Stanley M. Rowe, Jr. of Cincinnati and Weekapaug, R.I. He was doing research on the letters of his ancestor, Thomas M. Day, and he wanted to know more about Walnut Grove, an 85-acre property that had belonged to Day's brother, James Ingersoll Day. Fortuitously, I found the name on the famous 1868 Beers map of "Stoninington." Walnut Grove comprised a tract north and west of Lambert's Cove, including land north of Route 1 between North Main and North Water streets. I found many deeds in the town land records. I also began to be interested in the history of the family of James Ingersoll Day, who had built his house at the same time that the two Palmer brothers -- Captains Nathaniel B. and Alexander Smith Palmer -- were building their house at Pine Point.

There was a long trail to the next discovery. In the early 1990's, Emily Lynch, always a good source of out-of-the-way information, told me about Ann Bridge's family memoir A Family of Two Worlds(published in England as Portrait of My Mother). Ann Bridge was the pen name of Mary Dolling Sanders, daughter of Marie Louise Day, the youngest daughter of James Ingersoll Day and his wife, Sarah Armitage Day, of Walnut Grove. Marie Louise had married an Englishman, James Harris Sanders, and had gone to live in England. Her daughter, Mary Sanders, in 1913 married Owen O'Malley, a British diplomat who retired to Ireland.

Eventually, I tracked down Jane O'Malley, Ann Bridge's daughter, by then an elderly woman, in County Mayo, Ireland. Through her I met, by mail, Benita Stoney, a writer working on a biography of Ann Bridge, who told me about letters of James Ingersoll Day at the National Library of Ireland in Dublin. When I was in Ireland in October 2000, I went to Dublin to read those letters myself.

The Day letters in Ireland

In the O'Malley papers at the National Library of Ireland I found four letters written by James Ingersoll Day from New Orleans. Three were to his good friend Captain Alexander Smith Palmer, and the fourth was to Captain Charles Hewitt Smith, who had sold him the Quanaduck land.

The first letter, dated January 23, 1850, to Alexander Smith Palmer, discussed building two boats to be sent to New Orleans, the first a clipper ship to be "built after a model made by Fish of New York," the second a boat to be "used by [Day] for fishing in the shallows of the lake" (probably Lake Pontchartrain in New Orleans).

The second letter, addressed to Charles Hewitt Smith, is dated May 25, 1850, and has to do with real estate in Stonington. We know from the land record that on January 1, 1851, Day bought "48 Acres 11 1/4 Rods" from Smith (Stonington Land Records, Liber 25, page 88), the Quanaduck property. From this letter we also learn that Captain Alexander S. Palmer was Day's agent in these matters.

The third letter, dated December 18, 1850, was written for Day by his secretary, because Day had been injured in the explosion of the "new low-pressure towboat" Anglo-Norman on December 13 (New Orleans Daily Picayune, December 14, 1850). This ship had belonged to the Star Line, owned by J. W. Stanton & Co. of New Orleans.

J. W. Stanton and his brother, Charles T. Stanton, later built another of the stately homes, at the southeast end of Lambert's Cove (today 229 North Main Street, Linden Hall), near that of their brother-in-law, Alexander S. Palmer. A partner in their firm was another Palmer brother, William Lord Palmer, who ultimately retired to Stonington and lived at Redbrook (325 North Main Street) in the 1870s. In the news report, James I. Day is reported to have been "slightly injured"; he was certainly shaken.

By the time this letter was written, news had reached New Orleans of the loss to Alexander Smith Palmer of his house at Pine Point on November 15, 1849. A maid had gone to her third-floor room, and accidentally had brushed her candle against a summer dress hanging in the stairwell. Fortunately the family escaped with their lives. Day's secretary writes:

With regard to your house, he regrets very much to hear of its destruction by fire, but felt there was one consoling reflection: that it was effectually put out of the way. He has examined the plan for the new one -- and does not see that he can improve upon it except to throw all the chimnies [sic] in the body of the house --as it makes the house much warmer, & it can easily be done without much alteration to the plan. As soon as he is able to draw, he will send you his plan for his own house from which if in time, you can procure some ideas...

It appears from this that the Palmer family had already been well along in planning to build a larger, "more modern" house.

The fourth letter from James Ingersoll Day, again to Alexander S. Palmer, was written on December 23, 1850. This letter reveals that the Palmers were working on plans with a Mr. King, who was also involved in the planning of Day's house. This is a first indication that, contrary to previous assumptions, an architect designed the Palmer house. Day wrote:

In the meantime I have this evening traced out copies of my plans for my house to send you herewith thinking it probable that you may get some ideas from it to be of service to you. I have bestowed a good deal of thought upon it, and do not think it can be improved on very much. It is probably a larger house than you would care to build but its general arrangement could be worked into its compass. The chimneys all being in the Body of the House, makes a much warmer house in winter. The manner of construction you suggest, I shall probably adopt to Bricks between Post. If you should show these sketches to Mr. King, you might let him make an estimate upon it at the same time he does upon yours. If he wishes he can write me about the particulars that he might want, I shall probably be on about the 1st May next or middle certainly. I would call your attention to the arrangement of my Bathroom as being convenient to hot water and can be warmed by the fire of the kitchen for winter use and more accessible to all the inmates of the House. The Basement story I purpose to raise about 4 feet or 4 1/2 feet above the top of the Ground, thus making it half above and half below, with thick stone walls. Rough stone except perhaps the front face, but I have not as yet thought much about the details of my plan. The inside finish I shall want of plain genteel style, nothing very extravagant, probably such as you would adopt.

In the Palmer house, the plan for interior fireplaces was not adopted, although the raised basement was. The Day house eventually had thirty-five rooms, in "Hudson River Bracketed Style" according to Ann Bridge in a letter to her cousin, Decca Halsey, written on November 10,1953 (Harry Ransome Archive, University of Texas at Austin). It had a grapery, stables, and barns, and in 1858 the annual report of the New London Agricultural Society reported that the house was a "very large edifice in the pointed style, designed by W. King, Esq., architect of New York, and thoroughly built at the cost of twenty thousand dollars. It is furnished with water, and gas manufactured on the premises, and has all the conveniences and comforts of a first class house in the city, destined for a gentleman of means with a large circle of friends and kindred." (Stonington Mirror, October 13,1933)

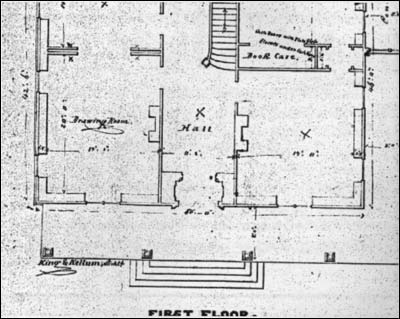

A careful search of census records failed to produce the "Mr. W. King" of the 1858 report. Luckily, plans for another stately home of Lambert's Cove, the house built (1857-1859) by the two Stanton brothers, Joseph Warren Stanton and Charles Thompson Stanton, provide his identity. On the first-floor plans for this structure was written "King and Kellum" at the bottom of the page, in a tight copperplate hand.

The Avery Library at the Columbia University School of Architecture confirmed that the principals were Gamaliel King and John Kellum, both distinguished architects, who practiced in Brooklyn from 1846 to 1859, mostly from Fulton Street, and who also had offices in Manhattan at 179 Broadway from 1855 to 1859.

Gamaliel King was born in Shelter Island on December 1, 1795, to Abraham King and Bethia Parshall King, and moved to Brooklyn as a young man. On June 19, 1819, he married Catherine Oliver Snow, daughter of John Snow and Catherine Oliver Snow of Brooklyn, and with her had five children, four of whom lived to adulthood.

His architectural career began in the early 1820s. In 1823 he was commissioned, with Joseph Moser, to build the York Methodist Episcopal Church in Brooklyn, an offshoot of the Sands Street Church; it was dedicated on June 6, 1824. In Spooner's 1824 directory for Brooklyn, Gamaliel King was listed as a "builder, building trades" at 11 Middagh Place. He was also at the time "Assessor of the village [of Brooklyn], Fireman No. 2 Engine Fire Department, and Trustee of the Firemen." The following year, he was at Pineapple Street, corner of Hicks, no longer assessor, but instead "Trustee of the Apprentices Library Association." In 1826, he was at Orange Street, as a builder, but in 1829 he was at 119 Fulton Street as a grocer, with a house at 81 Clark. In 1830 he was still listed as a grocer, but also as the local "inspector of Lumber."

By 1833 he must have completed the transition from builder to architect. In Architects in Practice in New York City 1840-1900 (by Dennis Steadman Francis, for the Committee for the Preservation of Architectural Records) he is listed as an architect at 98 Orange Street in Brooklyn from 1835 to 1842. In 1838 he designed the Church in Brooklyn known as St. Paul's, St. Peter's, Our Lady of Pilar Church, on Court Street at the southwest corner of Congress Street (AIA Guide to New York, 2000). By 1873 he claimed he was an "Architect Est'd 40 years. Good business. G.K. and J.H. Cornwell jr." (Cornwell -- or Cornwall -- may well have been his son-in-law, or a grandson: his daughter, Mary Elizabeth King, born in 1822, married a James Cornwall, who died in 1883.)

In 1846 he took as a partner a young carpenter, John Kellum of Hempstead, Long Island (1809-1871), who in time outstripped his mentor by becoming the architect for Alexander T. Stewart, the department store magnate. Kellum designed Stewart's marble mansion at Fifth Avenue and 34th Street and the block-wide store at Broadway and 10th Street, both in Manhattan, and at the time of his death in 1871 was laying out Garden City, a 7,000-acre tract in Hempstead that Stewart had bought. He also was co-designer of the New York County Courthouse, known as the "Tweed Courthouse" after William Marcy "Boss" Tweed, who commissioned it and profited from its construction.

By 1850, when James Ingersoll Day and Alexander Smith Palmer began to plan their houses, Gamaliel King's reputation was well established. In 1835 he had entered a design competition for Brooklyn City Hall, and he came in second. Still, he was named superintendent and resident architect for the winning entry, but the Panic of 1837 delayed the project. In 1845 a second competition was begun; King emulated the plans of the first winner and again placed second, but the next day a revote gave him the job. This building was built between 1846 and 1848, and put King in the public eye. (Jeffrey I. Richman, Brooklyn's Greenwood Cemetery, New York's Buried Treasure, 1998).

There must be many houses in Brooklyn still standing that were built by Gamaliel King. Unfortunately King worked before construction permits existed, so the only knowledge of his work is by chance through manuscript sources or plans that were kept in the houses he built, according to Christopher Gray, architectural history writer for The New York Times. It may be that the three houses on Lambert's Cove, the Day house (destroyed after the hurricane of 1938), the Captain Nathaniel B. Palmer house, and the Stanton house, known as Linden Hall, are the only documented houses attributed to King still standing today. It is also likely, but not yet documented, that the house now known as Cove Lawn (259 North Main Street), built in 1856 by the youngest Palmer brother, Captain Theodore Dwight Palmer, was also designed by Gamaliel King.

King and Kellum went on to design other public buildings. They built the 1857 Cast Iron Cary Building at 105 Chambers Street, the 1859 Friends Meeting House on Gramercy Park in Manhattan, and a store for Thomas Hunt in Brooklyn. In Christopher Gray's article on the Cary Building (The New York Times, July 16, 2000), he says that "Gary had built cast iron storefronts on Fulton Street in Brooklyn and Pearl Street in Manhattan designed by the architects King & Kellum."

In 1859 Kellum left the partnership to join forces with his son, and Gamaliel King continued on his own, with headquarters in Brooklyn. Always public-spirited, in 1857 he was part of a commission to construct a plan of sewage for the City of Brooklyn, and he later became head of the water and sewerage department. King continued to design public buildings: in 1859 he prepared a plan for the Free Church of St. Matthews on Throop Avenue, which opened for services in February 1861, and is credited with the Washington Square Methodist Church in Manhattan (1859-60). In 1861 he designed the Kings County Courthouse building with Hermann Teckritz; this building was torn down in 1961.

At the time of his death, on December 6, 1875, the flags at City Hall flew at half staff, and the commissioners attended his funeral (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 8,1875). Jeffrey Richman quotes a contemporary who described him as "a man with a good deal of cleverness, great industry and a touch of genius." The AIA Guide to New York City calls him a "poorly remembered architect."

Further Stonington documentation

Rather than relying solely on the reference in James Ingersoll Day's letters in Dublin, I looked at American repositories to find further evidence of Gamaliel King's involvement with the houses of Lambert's Cove. The Palmer-Loper Papers at the Library of Congress revealed no letters to or from Gamaliel King, but in Stonington, fortunately, there were on file in the Nathaniel B. Palmer house invoices from the building of the house, dating from 1851 and 1852.

Most of these had to do with workers from Stonington, but there was one invoice from a plumbing supplier in Brooklyn, Peter Milne of 133 Fulton Street, dated November 18, 1852. At this time King's office was nearby, at the corner of Fulton and Orange streets. The bill came to $622.78, and is countersigned by "G. King" and dated April 28, 1852, and "Stonington Conn." It included "board and travelling expenses $39," washtray plugs, and brass pipes. Among the more important items were "1 flat pan Water Closet complete $18, 3 marble pattern wash basins with over flows $7.50, 1 ditto without $2.00, 1 copper lift force pump $23, 1724 pounds of lead pipe $103.44, Italian veined Marble slabs Cutting 4 holes and boxing $46.76, 4 wrought iron keys and engraving $16." This appears to confirm that King was not only responsible for the purchase of this material, out also that he was in Stonington to oversee its installation.

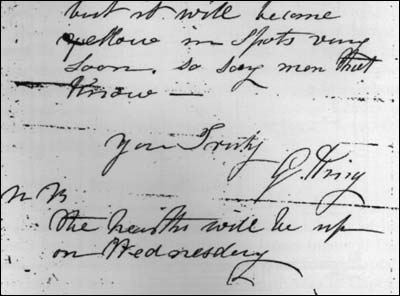

Another invoice, from a New York firm, was in the file at the Palmer house. This was for "Mr. Stanton." It was dated October 11, 1858, and was from the firm of John Shuster, a marble cutter, of 140 Court Street, between Pacific and Amity in Brooklyn. This too was signed by "G. King." Additionally, there is in the possession of Mr. and Mrs. C. Lawson Willard, the present owners of Linden Hall -- the home of J. W. Stanton and his brother, Charles T. Stanton -- a letter from Gamaliel King dated August 9,1858. Interestingly, the handwriting in this letter resembles that on a plan for the Palmer house grounds, which heretofore has been attributed to Alexander S. Palmer.

Mr. J.W. Stanton

Mr. Shuster will Furnish the Mantles for the following Prices

Brandon Marble

Moulded as the Mantle you

first saw at Shuster's

Statuary 1 1/2 inch thick $85 each $95 each 1 1/4 $75 $85 1 $65 $75

Tennessee Marble

Lisbon pattern $60

California 85

Second story front rooms

Italian Veined Marble $23

rear rooms: 20

The above Prices includes all Expenses Except Freight & Men's Passages.

My Opinion is that you had better have the Italian Statuary in the two Parlours, and the Coloured Marble in dining rooms, the white is so easily Coloured with Oil or other matter. As to Brandone marble it looks very well while clean and new, but it will become yellow in spots very soon. So say men that know.

Yours truly,

G. King

NB: the hearths will be up on Wednesday

Note dated August 10, 1858, in reply (at the end of the letter):

Will take two Statuary mantles for Parlours,

D[itt]o in 2 California d[itt]o for Dining Rooms

Same Pattern as we saw at Shusters, and the white must be pure, & the California must be as the sample we saw at Shusters, the Pattern same as above

Chamber mantels Italian Vein.

Let Mr. Shuster hurry with this, JWS [J. W. Stanton]

It is interesting to have the imprimatur of this architect thus confirmed. In Old Brooklyn Heights: New York's First Suburb (1979), Clay Lancaster describes Gamaliel King's new City Hall (1846), and goes on to write of the effect of the Greek Revival style on domestic architecture. Although his reference is to the Brooklyn Heights row houses, many of the stylistic features came to Stonington with the houses on Lambert's Cove:

The style of the new city hall supplanted the Federal in the evolution of the row house. For the most part it made use of the higher basement, which henceforth included the family dining room on the same floor with the kitchen, leaving the two rooms of the main level to serve as twin parlors. There was a new sense of interior spaciousness. Ceilings were made higher, and a screen of columns or pilasters flanking the wide sliding doors between the parlors allowed them to be thrown together into a single large apartment. The recessed front entrance was introduced, forming an intervening volume between outer and inner space. Houses were usually increased to three full stories above the basement, the third floor windows sometimes worked into the frieze of the entablature.

In an earlier reference to the Greek Revival style (1834-1860), Lancaster writes:

The Greek Revival style was heavier and more masculine than the Federal, in part due to technical advances, whereby steam-powered machinery took over much of the work formerly executed by hand. The architect, therefore, became the designer of details as well as the planner of the building as a whole, and this consolidation of the two separate functions of the builder and decorator into a single individual made for a greater design unity.

Certainly there is a unity in the Day and the Stanton mansions: a photograph of one could easily be confused for the other. The details in the Palmer house are reflected in the two houses across the cove. One's real regret is that there is no record to date left of Gamaliel King's domestic architecture in Brooklyn, Manhattan, and elsewhere. Perhaps in time this will come to light, but until then his Stonington houses appear to be his only domestic monuments.

Acknowledgements

Jai Lin Wong, Brooklyn Collection, Brooklyn Public Library

Sean Ashbey, Brooklyn Historical Society

Ted Goodman, reference librarian, Avery Library, Columbia University

Andrew S. Dolkart, architectural historian, Columbia University

John Cashman, Greenwood Cemetery historian

Jeffrey I. Richman, author, Brooklyn's Greenwood Cemetery: New York's Buried Treasure, 1998

Manuscript collection, National Library of Ireland, Kildare Street, Dublin

William N. Peterson, Mystic Seaport

Clay Lancaster, architectural history writer, The New York Times

Books consulted

Art and the Empire City: New York 1825-1861. Edited by Catherine H. Voorsanger and John K. Howat. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000.

Brooklyn's Greenwood Cemetery: New York's Buried Treasure. By Jeffrey I. Richman. Greenwood Cemetery Inc., 1998.

Garden City, Long Island in Early Photographs 1869-1919. By M. H. Smith. Dover, 1987.

Gotham: a History of New York City to 1898. By Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace. Oxford University Press, 1999.

New York 1880: Architecture and Urbanism in the Gilded Age. By Robert A.M. Stern, Thomas Mellins, and David Fishman. Monacelli Press, 1999.

Old Brooklyn Heights: New York's First Suburb. By Clay Lancaster. Dover, 1979.

Old Brooklyn in Early Photographs 1865-1929. By William Lee Younger. Dover, 1978.