THE TWILIGHT OF RURAL LIFE

The Dissolution of Mystic's Stanton Williams Farm

By Rudy J. Favretti

(From Historical Footnotes, May 2005

Rudy J. Favretti is a professor emeritus of landscape architecture, University of Connecticut, and author of Jumping the Puddle (2002). He wrote "Where the Atwoods Came From" in Historical Footnotes, November 2003.

Thomas Jefferson's plan for an agrarian society for the new nation had already dwindled to a dream one hundred years later. By 1890, industry and technology had burgeoned so that only 50 percent of the population was needed to produce food and fiber for the whole nation, instead of over 90 percent, as it was when Jefferson first promoted his ideal.

All about them, people were reminded of the situation: trains whistled in the distance, farmers mowed and raked their hayfields with horse drawn machines and used steam driven harvesters; the phone and electric light were out of their inventors' heads and on their way into homes. And these were just a few of the advances of science. Everyone was excited about it. Much of the adulation came from those who attended the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, where newfangled machines and equipment were on view in the huge Machinery Building. Even art exhibits in the Main Building showed the influence of technology -- significantly for our area: textiles woven on fast machine looms.

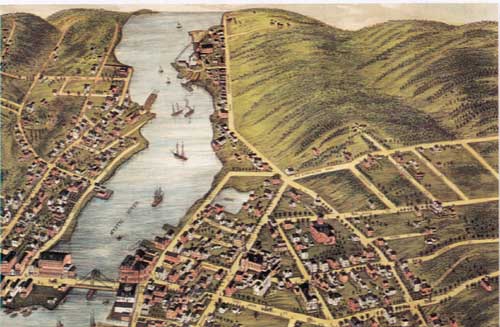

Families in Eastern Connecticut did not need to travel to Philadelphia to be reminded of the onrush of technology and industry. It was happening in microcosm on what was called Greenmanville Avenue, or by its old name, the Road to Mystic.

The seeds of change had been planted. On the west, or river, side of the road was a textile mill built in 1849 by the Greenman brothers to supplement their declining ship-building enterprise. It was so successful that the wooden mill building was augmented by a major brick structure in 1862. (This survives as the Stillman Building at Mystic Seaport.)

On the east side of the Road to Mystic was more than a mile of farmland, which reached from what was the Stonington Road (now Mistuxet Avenue) to Elm Grove Cemetery. This farm also stretched a mile or more to the east, over the ridge, all the way to the Denison property in Pequotsepos. The entire tract, more than five hundred acres, embraced two marshes along the Road to Mystic. The large tidal one was filled in the 1950's and is now Mystic Seaport's south parking lot; the smaller northern marsh is the north parking lot, opposite Seaman's Inne. Up over the hills to the east were fields of grain and hay, and beyond were walled pastures, woodland, and a vast system of wetlands surrounding Pequotsepos Brook.

The owner of this spread was Joseph Stanton Williams (1802-1889), son of Captain Elias Williams (1773-1809) and Thankful Stanton (1794-1861). To digress a bit, Captain Elias Williams was a great-great grandson of John Williams, who settled in Stonington on the south side of Quoketaug Hill in 1685. He was also first cousin to Charles Phelps Williams, a prominent Stonington businessman of the nineteenth century. Thankful Stanton was great-great-great granddaughter of Thomas Stanton, the Indian interpreter, who settled in Stonington in 1651. Much of Joseph Stanton Williams's farm was inherited, though some was purchased. It is quite possible that a portion was acquired through his wife's inheritance, since she was Julia Gallup, and the Gallups were early Mystic settlers, with land at the north end of the Williams tract.

Joseph Stanton Williams, or "Stanton," as he was called, referred to two farms in this tract in his will dated October 6, 1888. According to the probate records, he left Elm Tree Farm, "my home farm, stock, and farming tools and carriage, and the crops gathered, or standing and growing, and all household goods and furniture" to his son Elias. The Lower Farm, as he designated it, with a house and furniture, barns, and a rental house, was left to his other son and namesake, Joseph Stanton Williams Jr., except for the blacksmith shop at the southwest corner (now the corner of Greenmanville and Mistuxet), which he left to Elias, along with his "slip [pew] at the Road Church, so called." Stanton Williams also remembered his daughter, Julia Ann Foote, wife of Solomon Foote, with certain household memorabilia.

His three granddaughters -- Julia Gallup Foote, Lydia Morgan, and Anne King -- received sums of money. His grandsons Gordon and Charles Williams received half of the "ship yard lot," and the other half went to his daughter, Julia Ann Foote. (To digress a long way, I knew the granddaughter Julia Gallup Foote as a frequent substitute teacher at the Broadway School in Mystic. A sweet, kind woman, she was a former penmanship teacher. She had huge feet and wore men's shoes, most uncommon at the time. As a child, I thought she was named Foote for the size of her feet.)

The Greenman mill across Greenmanville Avenue was a harbinger of the forces that would affect the subsequent subdividing and development of the Williams farmland. In another half century, Jefferson's agrarian dream was over, ended by changing land needs as politics and technology left rural life behind. Things moved even faster after that. Today, with modern technology, less than 5 percent of the population is farming, raising food for much of the world.

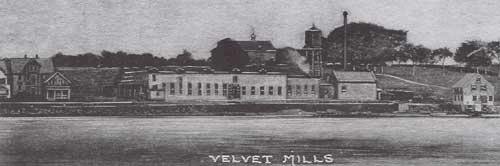

Even in 1889, with Stanton Williams's death, it did not take his heirs long to fall in with the times and begin selling their farms. In 1897, over 140 Mystic citizens became stockholders in the Mystic Industrial Company, the purpose being to erect a well equipped factory. The Mystic Board of Trade encouraged this venture, having already met with Thomas, Ernest, and John Rossie, from Suchtein, Germany. They were interested in moving their velvet weaving business to the United States to circumvent the costs inflicted by Washington's protective taxes, specifically the McKinley Tariff Act of 1890. (The Wimpfheimer family had already established its mill in Stonington in 1892; see Historical Footnotes, November 1992). Elias Williams became a stockholder and gave two acres of his farm to build the mill, which opened in 1898, just nine years after Stanton Williams died. (The Rossie Mill has been adapted and today serves as curatorial offices for the Mystic Seaport.)

With the Rossies came an influx of German workers. A large square mill house was built on Velvet Lane, just north of the mill. It provided several apartments where immigrants could live until they saved enough money to buy a lot from Elias Williams along Greenmanville Avenue, north and south of the mill, and construct homes. Rossie Street and Bruggeman Place were partly laid out, and a few houses built. But from 1898 on, house after house was built, until the outbreak of World War 1. The land records show new householders were named Wilhelm, Weimer, Donsbach, Bruggeman, Rossie, Hermes, Brunke, Weyer, Geisers, Thissen, Imdahl, Spicks, Litterscheidt, Hockschill, Eidersheim, Keller, Nauen, Menge, Cremers, Fiedler, and Frensch.

Long hours in the mill created a need for a place to socialize at the end of the day, as well as with the family on weekends. The German social society Frohsinn was formed in 1905, and soon thereafter the club house was constructed. It still stands as the German Club, opposite the main entrance of Mystic Seaport.

A showpiece soon sprang up between Rossie Street and Bruggeman Place to rival the Greenman houses across Greenmanville Avenue. This was the large stuccoed house of Ernest Rossie (1883-1931), now the Dickerman House of Mystic Seaport, and a companion, the house of Peter Bruggeman (1857-1910), now the Munson Institute. Rossie, of course, was part owner of the mill, and Bruggeman was one of his executives. These two houses shared a large garden that was a virtual arboretum of both evergreen and deciduous trees and shrubs, with a large pool and fountain in the center. The garden was designed as a focus to be viewed from both houses and also for passers-by to enjoy from the street. It, too, is now a parking lot.

Starting in the early years of the 20th century, another influx of immigrants arrived to settle and purchase lots from Elias Williams. These were Italians, mostly from the valley of Zoldo in the Dolomite Alps of northeastern Italy (see Historical Footnotes, August 1981, May and August 2003). Many of the men were skilled blacksmiths who found employment in the shop of the Rossie Mill, repairing and making parts for the looms. Others were craftsmen who built houses or worked in Mystic's shipyards. Their names were Santin, Brustolon, PraLevis, Cini, Pasqualin, Scussel, Panciera, Fain, and Favretti -- my family. Some blacksmiths switched to repairing and selling automobiles, and the Santins soon built a garage (now the Art and Custom Framing Center). Several years later, Joseph Brustolon put his garage into the blacksmith shop that Elias Williams had owned at the corner of the Lower Farm, though it had been expanded into a larger structure. Most of the Zoldani settled on Bruggeman Place and Rossie Street, though another small colony purchased houses on Mistuxet Avenue, just south of the Williams Lower Farm.

Joseph Stanton Williams Jr. also sold portions of his Lower Farm, but instead of selling off individual house lots, in 1905 he sold a large tract to a company called the Northern Land Company of Hudson, based in Middlesex County, Massachusetts. This tract extended north from Mistuxet Avenue along Greenmanville Avenue. Alden and Williams streets were later built within this piece to accommodate more houses; the entire parcel was known as the Hillside Park Tract.

For twenty years land along Greenmanville Avenue and up the new side streets was developed rapidly, but then World War I caused a delay. Everything along Greenmanville Avenue from north of the mill south to Mistuxet Avenue had been developed, excluding the tidal marshes, as well as the Rossie, Bruggeman, Williams, and Alden side streets as far as the base of the hill. As soon as the economy improved after the war, more houses were built up the hill to the start of the ridge, except for Bruggeman Place, which continued a bit beyond.

Elias Williams's widow had sold the remainder of Elm Tree Farm to the Rossies, and the heirs of Joseph Stanton Williams Jr. sold off the fringes of the remainder of Lower Farm, reserving a few acres around the homestead. But these were all to be sold off within a few years.

What exists of the original farm today? The house and barn at Elm Tree Farm were destroyed, and a new house sits on the site of the homestead, just south of the John Rossie Field at the end of the present Rossie Pentway. Some large stones from the ramp to the barn loft are evident in the wall of the little structure that serves the ball field. The house at the Lower Farm still stands as 45 Mistuxet Avenue, though the barns fell in the 1938 hurricane. The tenant house at the Lower Farm is now 25 Mistuxet Avenue, and the blacksmith shop, which grew and became Foote's Garage, is now even larger as the Coogan Gildersleeve Appliance Center. (The Coogans are descendants of Stanton Williams's granddaughter Lydia Morgan.)

The great depression that began in 1929 halted development of the two Williams farms, and as the economy was beginning to recover in the late 1930's, another war came. But for people settled there, the slowing of building was a bonus, because behind their houses to the east was a virtual natural park of almost 300 acres, much of it belonging to the Rossies. Families in the neighborhood hiked there, studied the flora and fauna, gathered blueberries and hazelnuts, played cops and robbers on the ledges, waded in Pequotsepos Brook, gathered daisies to make garlands for commencement at the Broadway School, built huts and playhouses under the canopies of old apple trees, survivors of the orchard, tapped maple trees when the sap began to run, and enjoyed hours of outdoor activity, all sanctioned by the owners.

In the center of this paradise was a very large white oak tree, still standing at 4 Whaler Road, but in a state of decline. Here John Rossie had created a large picnic ground on a level rise; children could play on the ledges nearby. Here the Rossie Velvet Company held its annual picnic for the employees, inviting workers from other textile mills across the state. At Mr. Rossie's death in 1966, The New London Day reported: "Mr. Rossie's tall figure was a familiar sight at the head of the line when the annual Rossie picnic began with a street parade through downtown Mystic to the picnic grounds in Rossie woods. Besides the several hundred employees, at least half the children of the village, by conservative estimate, clustered around the fringes at the daylong festivities."

All of this came to an end at the start of World War II, in part because of the War, but also because the Rossie Velvet Company was declining in productivity. It was finally sold in 1955, and closed in 1958. Starting in the early 1950's, the land remaining in both farms was subdivided for upwards to one hundred houses. Were the real estate development of Stanton Williams's farm to take place today, with the march of technology to bulldozers and backhoes, both farms could be swallowed up within a few years instead of more than half a century.

Sources consulted: Homes of Our Ancestors in Stonington by Grace D. Wheeler, Salem, Mass. 1903; Stonington vital, probate and land records for pertinent years; Historic Buildings at the Mystic Seaport Museum by William N. Peterson and Peter M. Coope, Mystic, Conn., 1985.