GIRLHOOD MEMORIES OF A CABIN BOY

By Dorothea Hewitt Gould

(From Historical Footnotes, November 1980)

My stepfather, Captain Richard Tillotsen, was a native of Port Jefferson, Long Island. He married my mother in Taunton, Massachusetts, whence I came, with her, to Stonington in 1916. We rented rooms at 96 Water Street in what is now Mrs. Bartram's house. It was then the Wampossett Inn, and meals were served there. Later we had an apartment in the brick house at the corner of Grand and Gold Streets, which, incidentally, is made of bricks used for ballast in some of the ships that came in to Stonington.

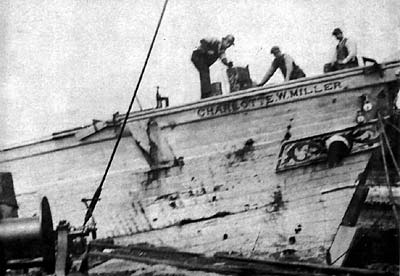

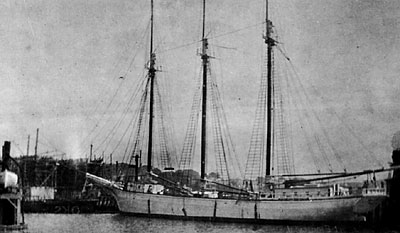

My father bought a three-masted schooner at the U. S. Marshal's sale named Charlotte W. Miller. She had been rammed by an American submarine out there in The Race, so my father bought the schooner and had her towed into Stonington to be repaired. All the work was done by local artisans, the finest shipwrights. They aren't around now. The last one was Frank Newton, the chief carpenter, and he did beautiful work. He died a few years ago. It took quite a while to repair the huge gaping hole near the starboard bow. My father, being a shipbroker as well as a sea captain, sold shares in this schooner. The man who bought the most shares was William H. Draper of Providence, Rhode Island, and the schooner was renamed for him.

Finally the day came when she was all ready to go, and she was really a palace. Her sails were bent by sailmaker John Bailey of New London. There were hand paintings of ships on the paneling in the after cabin where my father, my mother, and myself had our quarters. My bed was gimballed so that when the ship rocked it would remain level. The lamps were gimballed too so that they remained upright.

So the day finally came when we stood out of the harbor; the fair wind came and off we went. People lined the shore as we left to head for Erie Basin in New York to undergo inspection. This was during World War I, and in order to ship aboard everyone had to have a category. My father was the captain; my mother had the category of ship's cook; I was the cabin boy. There was also a first mate, and two sailors. One of the sailors, Alec Weisemeir, came from Stonington.

My duties as cabin boy were: first, charge of the ship's log, which was weighted to be thrown overboard if we were attacked. This sounds corny, but it was war time. The second duty was to memorize a book which had the colors of all the pennants to be raised on entering and leaving harbors, depending upon the message received from shore. These pennants were many colors and designs and were quite large. I was in charge of folding them properly in the order they were presented in the book. Also I was in charge of putting them on the halyard upon entering and leaving harbors. I don't remember any other time when we used them. They were folded and put in a locker purposely made for the pennants.

Then there was the lazarette. My mother paled at the thought of me going down into it, but that was where the "salt horse" was kept. Armed with a large knife, I was charged to go down into the little lazarette and cut off the salt horse. It was bully-beef, really, like they had during the war in England. But my father called it salt horse. I've forgotten what magic my mother performed on it -- some of the salt was taken out in the process. My mother had never even boiled water before she became the cook of our ship. She learned everything from my father, who was an excellent cook.

I had to learn to box the compass (thirty-two points on the card), stand my trick at the wheel, and name every line and piece of canvas. But my mother put her foot down when it came to the chore of climbing the ratlins. She would not hear of that; that was up to the sailors. She wasn't going to have her daughter up there, and I'm glad she didn't; I'd probably have fallen overboard, because I'm scared to death of heights.

After the William Draper, I was cabin boy on the Nantisco as well, her name a contraction of Nantucket Island Company. I only went one summer on her, just enough to go into Nantucket and see how much I loved it. We went all around, looked in the old houses and went to the shops and to the man who was making rope. He had hemp and sisal; it smelled lovely there. He was also making lobster pots and the funnels for them. It's funny -- I remember the different gift shops, and the cobblestone streets, but I don't remember what the cargo was, or why we were there.

Some cargoes I do remember. I hated Graselli, New Jersey. On that trip we carried barrels of chemicals, and I recall vividly having to sleep with a mask over my face so that I could breathe without that chemical smell. To this day I hate the smell. Fortunately that was a hold cargo, so that when the hatch covers were put on they deadened the smell somewhat. And fortunately we didn't stay there too long. I remember going ashore at Elizabeth, New Jersey, another port nearby. Dressed in my Sunday best, that was when my father decided I should learn to scull -- in my best dress. But I learned to scull the longboat, a dory, though my mother was aghast -- seems as though she always was. We went into town and I had my first banana split.

On another trip we went to a place in Maine (it could have been Vinal Haven) and bought a deckload of pine slabs, and once a load of sand. My mother didn't like that because it might shift and we'd roll right over. It had to be carefully put in the hold; they used hoardings, or boards, to keep it separated. Whatever profit the boat made was shared: so much for the boat, so much for the crew, so much for the shareholders, and whatever was left was ours, I suppose.

In bad weather we would anchor in back of breakwaters and that sort of place. We had doldrums, where you'd get out there and wait. What else could you do? Just wait. You'd have to give her her head and let her steer, and keep watch on the sails to see where they were filling from. I remember going through the Cape Cod Canal on the Nantisco, and reaching the outward side of the canal we struck an eddy and were in real danger of being capsized. It was so swift; such volume came at us, it was like a whirlpool, and even though we had everything battened down, cups and things were flying off and my father told me to get below, which I did. We came out of that, but even he was a little shaken by the experience because it was so sudden. You would know about eddies and things, but you wouldn't realize that they come upon you so quickly.

My mother did laundry on board with salt water soap. But we washed ourselves in fresh water collected in the cistern. We had bath nights twice a week. In the middle of the week and on Saturday I was immersed in the galvanized tub in the after cabin and scrubbed. And, of course, I had long hair. It was very long, very thick and in huge braids. My mother wanted it -- I wanted to cut it off. So the day I was 18, I had it cut off. I came home with those beautiful braids in my hand and she fainted dead away on the kitchen floor.

Clothing seemed to be the last thing that was thought of. You didn't dress for the occasion on shipboard. I just wore dresses that were no longer used for school. I never wore sneakers; my mother wouldn't allow it. She said they spread your feet. I wore what we called "Trot-Mocs," like moccasins. I always had a little white sailor's hat, a regulation navy sailor's hat.

We had a lot of good fish, and my mother learned from my stepfather how to cook it very well. Oh yes, and occasionally we'd happen to snag a lobster pot, too. Whops! Another thing that mother learned from my stepfather was how to cook a slice of ham that would melt in your mouth. That was to let it soak in molasses and water: lay it flat in some molasses, stir it around with your finger and let it stay for an hour or two, or overnight, and then fry it. That molasses did something to that ham.

And I remember going ashore somewhere up in Maine with my mother to gather blueberries on a little island. The deer were there and they were inquisitive. They came over to see what we were doing -- we were stealing their blueberries. My mother would make blueberry pie, of course, and what us New Englanders in those days called "blueberry slump" which is a dumpling with hot stewed blueberries poured over it. My mother used to say that the Shipmate stove in the galley "would cook with the fire out." It was the best stove in the world.

One of the sailors played the harmonica, but there wasn't much singing. My father was a strict sea captain. He was raised strictly, and everybody toed the mark and did their chore and that was it. But we used to gather in the evenings aboard some of the schooners that were anchored nearby, and that was great fun. We'd scull over to them, and they'd put on the coffee, and I would sit there and listen to the stories. Whether they were true or false, I didn't know, but they entertained me. One captain they used to tell about was so penurious that he would put the teakettle on the stove before he lit the fire, to get all the heat.

I was an avid reader. I read Tom Swift books that were given to me by some of the sailors, and Horatio Alger's From Rags to Riches. And I had to study, especially arithmetic. I hated it, still do. I couldn't cope with it, so Miss Durgin made me study all the time I was gone from school. Sometimes I would get myself nestled up in the bow and lie out on the bowsprit with a russet apple and watch the schooners come toward me. And, like you can tell somebody's car coming down the street, I could tell a schooner when she was coming along. I'd say "Here comes Zeb" (Zebulon Tilton) or "Here comes theRobert John Beswick."

My sailing days were mostly, of course, in the summertime, when I was on school vacation. I had to return to Stonington and get ready for grammar school, probably before Labor Day. I liked school, everything but the arithmetic. I stayed with many different people, and I was always requested to come back because I was a well-behaved lady and I helped with the dishes. My mother continued on, sailing with my father, during the winter months. But there weren't many trips during the winter, and I couldn't even tell you where they laid up. It was probably Boston, because the boat was registered in Boston. I don't know how they got along without their cabin boy, but somehow they managed 'till the next year.

This article was taken from certain reminiscences of Dorothea Gould tape recorded by Barbara Fertig, who, when she first came to Stonington, resided at Dorothea Gould's. Louise Pittaway collaborated with them in the construction of this article.